Are there parallel or alternate realities, or does reality consist of multiple realities?

Ridgewell, Thomas. “…in the remaining parallel universes: Meanwhile 3” Youtube, uploaded by Thomas Ridgewell, December 14, 2014. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DWM8g59Pkm4>

The reality of one who is blind is vastly different from the reality of a person who isn’t blind. What does the multiplicity of realities, the realities that differ from person to person, say about reality itself? Is there one, true, capital “R” Reality? It would appear not, as Helen Keller obviously experienced a reality vastly different from someone like me. Helen Keller was born dumb, blind, and deaf, making her sense her reality, her existence in a very peculiar and unique way from those around her. But it’s only peculiar and unique because it’s different from what some would call “normal” people, as if normalcy is measured by our abilities to see, hear, and talk.

That’s just it. There is no normal, ideal way of existing, of being human, or living in reality. We are not created to be the same, we do not fit so easily into the moulds that are constructed for us. Nor should we attempt to define a person by prioritizing what is ideal and what is not. Blindness to some, would be seen as an impediment, as a hindrance, something to be quelled and fixed, made straight, made normal. But who decided that being able to see is ideal? What factors came into consideration when it was decided that blindness is something to be fixed? When in fact, blindness is just another reality, another form of existence? It is a way of life, it is a philosophy, it is merely another way being human.

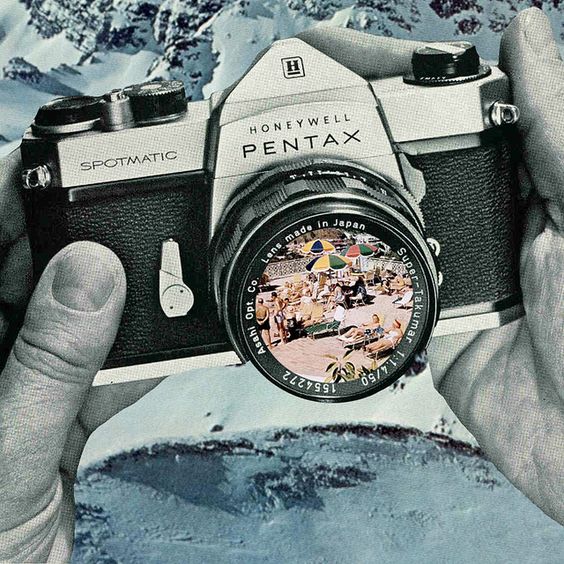

It’s interesting to think that an image can carry meaning, can “say” something; that it allows the viewer to peel back the paint on the surface, and delve past the superficial level on the canvas to the potentially infinite possibilities and ways it can be interpreted, speaks to the power images have, simply by presenting themselves to the viewer. Again using words. Language seems to always crop up when it comes to the human individual in relation to the “other” or the relation to the subject matter, in relation to all that individual perceives, how they exist in the world they exist in. Humans use language to comprehend the things they’re looking at; and similarity art – photography, artwork, images, representations – use words as well among their other mediums handy in their tool kit, along with the paintbrush, the platform the image is exhibited, the lens. Words are as present as the subject matter, almost as visible as the techniques in composition, words have a natural place in the artwork, in the image, with the artist, alongside the photographer.

How? When a painting or photograph is presented to a viewer, are not words needed to describe the emotions elicited? words are used to comprehend possible reasons for that particular angle, used to elucidate the possibility that the artist is commenting on something else, using metaphor to get a view or a certain opinion across, that the artist is conveying something to their viewers, and the artwork itself is words portrayed on a canvas, painting a narrative, sketching a convention, using words as shading, that each brushstroke is rhetoric, that every single detail – or lack of detail – is in fact “saying” something. And in turn, for us as viewers and spectators, in relation to an artwork on canvas or a photograph, we use language in a way to describe the impact of what’s being presented.

Photography can be defined many ways. It can be seen as “capturing” a fleeting moment. It can be seen as taking a leash and lassoing it around a moment to keep it from fidgeting. It can be seen as cementing a memory forever onto something tangible. Photography can be seen as a means of objectively witnessing a frame of time – it can state rather definitively: “THIS IS EXACTLY AND PRECISELY WHAT THIS THING LOOKS LIKE” presenting itself as a means to which people can view their world “accurately”.

The photograph. A technology that brags being able to capture a fleeting moment’s time objectively. It can be seen as taking a leash and lassoing it around a frame in time to keep it from fidgeting. Ostensibly, a photograph perfectly represents the facts, presuppose that it tames the subject matter, cements memories into tangibility, silences the noise, makes still the fluidity and ephemerality of the moment; immortalizing and making timeless mere mortals, fleeting weather patterns, finite entities all to the four wall confinement of the photograph. Pretty powerful stuff. Also quite manipulative. That a mere machine, a lens, can take life — something known to be fleeting, ephemeral, ungraspable — and put it on display rather concretely, almost like the way museums tend to take the past and put it in display cases, as if it is something knowable, something tameable.

Yet there’s so much more to photography than merely a means of objectively documenting. Photography is an art form in some cases, it is a way of life, but ultimately it is a tool, and certainly a powerful one that goes beyond the boundaries between fact and reality and falsehoods. In fact, photography reshapes the categories and truth and lie, reality and fiction, making their borders porous.

What’s interesting in my limited and amateurish experience with photography, is the same motif time and time again: that the camera lens never seems to accurately capture exactly what my eyes are witnessing. The lens of the camera doesn’t seem to have as much depth and detail as the lens of the human eye. This is a frustration that I’m sure many camera users face. What it does is replicate what the human eye witnesses, and by using different settings, different lenses, different apertures, shutter releases — essentially knobs in a machine — you can recreate an image of reality into multiple, varying forms, twisting and bending a moment in time into something sometimes wholly other than what it looks. The fundamentally fascinating thing about this, is that photography, based on this definition, dismantles the most important distinction in ontological philosophy: what is the distinction between reality and appearance, representation and actuality, and how do we tell them apart?

In a way, photography, like art and film, is a lie.

Below is a wonderful video on Ansel Adams by the nerdwriter1.

Puschak, Evan “Ansel Adams: Photography with Intention” Youtube, uploaded by Evan Puschak (nerdwriter1) on March 16, 2016. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7zcancgfDVg>

Capturing the mind’s eye.

Below is a rather daunting example of this interesting facet of photography: that it doesn’t’ always quite represent what we see.

This is Daguerre’s photograph, known to be his first, of a bustling city street in the middle of Paris.

But what exactly do we see? What are our human, limited, finite senses picking up? As human beings, obviously, the only way we can see ourselves, the people around us, our world, and our existence is through our own humanness. Inevitably, we can only contemplate and seek to understand fragments of our world through human senses, human understanding, the finite boundaries of the human mind. The interesting thing about this photograph, is not only that it is one of the first known photographs taken, but that with an exposure time of 10-15 minutes, Daguerre cannot, with his camera, take a “proper” photograph of the street in Paris.

You see, at the that time, the streets of Paris, after having gone extensive construction following the French Revolution, would have been packed with people. In this photograph of a Parisian street, there should have been numerous amounts of people walking up and down the street. But there isn’t. These streets of Paris, theoretically, would have been the perfect place for a flaneur to do his viewing. The shops would have been brimming with people, the public lounge areas were just beginning to become a fad. The street was so filled with people hurrying back and forth, walking up and down the street, that no one would have been sitting or standing still long enough to be captured by the camera. And henceforth, due to their inability to be still, they are completely wiped off the frame of existence, as if they were never there. Daguerre’s camera convincingly shows that no one was there, when in “reality” there would have been multitudes.

All we see here are two people who were standing still long enough to be captured by the camera.

A shoe shiner, and a figure having their shoes shined.

But what’s real? How can we possibly know? Is the camera lying to us, is its technological inability to capture a bustling Parisian street the reason why the street looks empty. Or is the street truly empty, apart from the two figures engaged in the shining of shoes. What did Daguerre really see?

To be continued